Health and growth – Quality AND quantity!

24.06.13

For most countries in the developed world, there is a pretty standard list of policy tools that gets drawn on to show government is doing something boost the economy. Periodically the catch phrases that politicians use tend to go in and out of fashion – sometimes it’s all about ‘innovation’, sometimes ‘productivity’ or ‘competitiveness’ (a term often misused). The current vogue seems to be ‘growth’. But, beneath the array of competitiveness or growth strategies, the real policy building blocks tend to be largely consistent. I find it useful to think of two buckets (this is, by the way, a slight caricature, and I’m not referring to specific governments or institutions, but this is very close to reality in most places):

1. Framework conditions

- Get the macroeconomics right. Low inflation, high employment etc. (There’s a lot that can be said about this, of course, but now’s not the time. Suffice it to say we have one of those objectives in place in Europe…the other, sadly, is more of a work in progress).

- Make sure you have well functioning-institutions that support a productive (and competitive) business environment: You might include the competition framework, intellectual property regime, rule of law and the like.

- Don’t over-regulate. Regulation is important of course, but it should be: kept to a minimum; burden on business should be reduced and, in some areas, by being outcomes rather than process-focussed regulation can be used to encourage innovation.

- Flexible and open markets. This is a bit of a catch-all, but for brevity’s sake I’m using it to capture ideas around flexible labour markets, openness to trade etc.

Once the framework conditions are in place there are various, more interventionist policies that can, to (sometimes vastly) varying degrees, get adopted.

- Support access to finance. Especially in small firms where there are market failures, for example, if the owners of a start up don’t have collateral to put up to obtain a loan they can’t grow – so governments can step in and provide a guarantee.

- Fund science and education. There’s usually good recognition that a qualified and skilled work force, alongside funding for basic research, is important for the so-called knowledge-based economy.

- Active procurement. As Governments themselves are usually a major source of demand in the economy attempts have been made to maximise the potential benefits of government as a ‘smart procurer’ this might mean encouraging innovative solutions or attempts to make sure that smaller firms get access to government contracts as much as larger firms.

- Other Innovation Policy such as knowledge transfer schemes, support for R&D, collaborative research funding or other types of public private partnership. The IMI is, of course, a very significant example of this.

And that’s pretty much it… Don’t get me wrong – all of the above are sensible and important areas on which Government should focus. But health is, by and large, missing from the list. And, increasingly, I think that’s a problem.

There are several reasons why health policy should have its place: improving productivity in the workplace; reducing absenteeism; addressing regional disparities in economic performance through focusing on health improvement etc. All subjects for future blog posts. Here, though, I want to focus on one issue: relationship between the quantity and the quality of life expectancy – and why that’s important for long-term growth.

Quality and Quantity

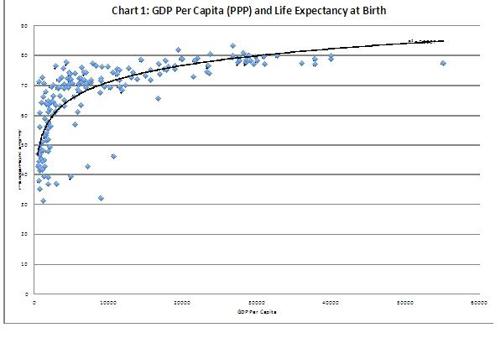

In the developing word, the story is different. Pick up any text on economic growth in poorer countries and the chances are you’ll find significant sections devoted to healthcare. This is not surprising. The relationship between life expectancy and wealth at poorer levels of the income distribution is without doubt. And it’s a two-way relationship: the richer a country is the more it can afford the sort of basic infrastructure, sanitation and medicines that save lives. At the same time, a healthier population is better able to take part in productive work generating, in turn, more wealth. But there comes a point where the relationship between life expectancy and wealth flattens out. Chart 1 shows this for 180 countries and it’s the impression created by this chart that, I think, lies behind the fact that economic policymakers have largely neglected health as a policy tool in richer countries until now.

Source: CIA Factbook

The trouble is, life expectancy is only one measure of healthcare outcome and, increasingly, it’s not the most important one if we want to understand how health policy can impact the economy. Quality of life – or more accurately I mean the amount of our lives that is not spent with some sort of illness or disability – not just the length of it, is important if we want people to at least have the option of staying in work, contributing to GDP. At very least, keeping people out of expensive hospitals or social care for as long as possible could be the difference between financially sustainable health systems and a major funding crisis.

We all know that Europe is facing a challenge of dealing with an ageing population. According to the European Commission there is likely to be an 11% decline in the size of the workforce by 2050, whilst at the same time the number of people over 65 will rise by 75%. What’s perhaps less well known is the fact that although we’re living longer we’re spending more of our lives in some sort of ill health.

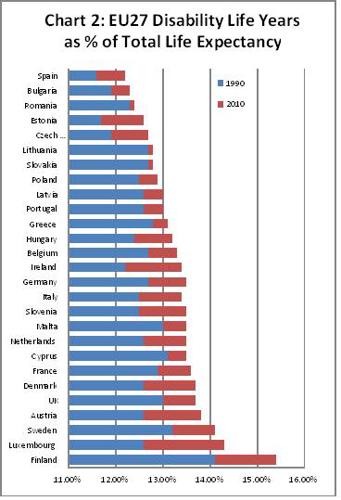

Source: Lancet: Healthy life expectancy for 187 countries, 1990–2010 (2010)

Chart 2 shows that, in the 20 years between 1990 and 2010, the proportion of people’s lives spent with some kind of illness or disability increased in all 27 countries of the European Union.

Reversing this trend ought to be a fundamental objective of mid to long-term growth policies for Europe. Policies that help us live healthier lives would help with the sustainability of public finance by reducing pressure on the costs of retirement. But they would also help maximise the productivity of European citizens during their working lives. There is an urgent need to debate what those policies might look like and how they can be made coherent with the rest of economic policy. We’re not starting from blank sheet of paper of course and there is much superb commentary on the need to upgrade our focus on prevention and healthier lifestyles etc. But the whole area needs more focus and needs to be recognised by economic policymakers as an essential enabler of a prosperous future for Europe.

Tomorrow at EFPIA, we hope to start a debate on these issues through our annual meeting. We invited Paul Krugman to give a keynote speech this year because we want to support the discussion that needs to take place about what Europe must do to come back to prosperity. We also have a top-class panel of healthcare academics, policy commentators and stakeholders to debate the issues.

Health might not be top of the list when it comes to growth policy, but it certainly merits a place on the list somewhere.

– Richard Torbett – EFPIA Chief Economist