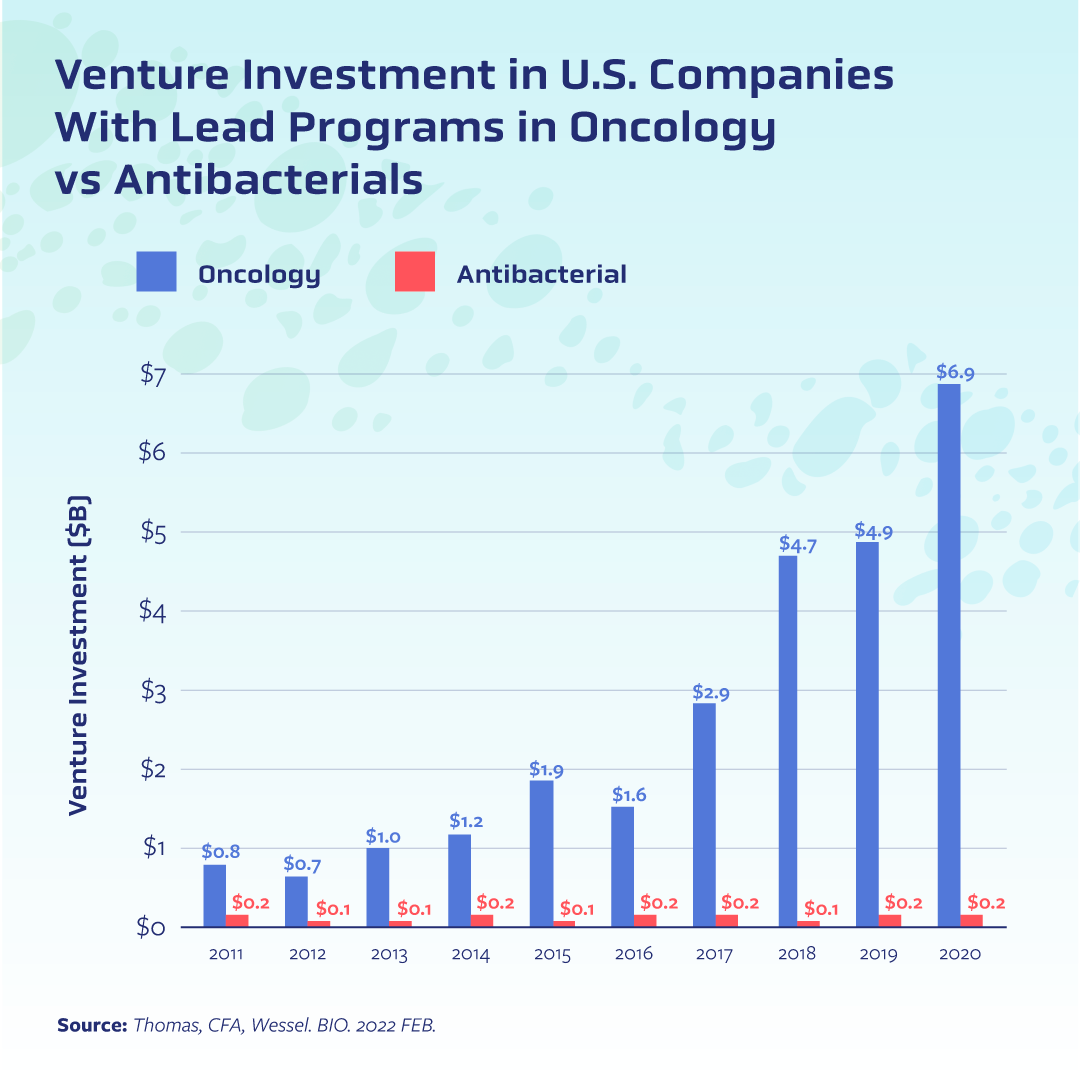

This paucity of private investment has stymied innovation[3]. More than four decades have passed since a new class of antibiotics has come to market, and it has been more than 20 years since a new antifungal class has made it from bench to bedside. Even when biotechs beat the odds and bring an antimicrobial into clinical testing—and in some cases all the way through the approval process—the market fails them[4]. One oft-cited case is that of Achaogen, the small biotech that earned approval of its antibiotic plazomicin only to declare bankruptcy soon after. Numerous other biotechs have faced similar challenges, including the French company DeInove which had an antimicrobial compound in Phase II testing but announced this winter it was closing shop.

Pull incentives can revitalise the market and uplift the numerous biotechs across Europe that are doing excellent science in the face of relentless financial headwinds. Through ambitious and forward-thinking policy action, policymakers can realign the intersection of commercial interests and public health needs in a way that accelerates innovation, ensures access to urgently needed medicines, and re-assures investors of the strength of Europe’s life sciences sector.

Already there is some momentum in Europe, but these efforts are fragmented and only address pieces of the problem. In Sweden, for instance, policymakers crafted a partially delinked arrangement to guarantee modest annual revenues and reduce reliance on sales. While a good step forward in addressing short-term market challenges, it does little in the way of incentivising the type of innovation that attracts investors. Other countries have attempted to tackle the value side of the equation; Germany and France, for example, have introduced attempts to account for AMR in existing reimbursement schemes. The UK has gone the furthest[5] by attempting to address innovation, access, and valuation. Ultimately, all of these have so far come up short in terms of addressing the long-term realities of antimicrobial resistance: bacterial and fungal pathogens will continually evolve resistance to new treatments, and the world needs meaningful incentives for a sustainable ecosystem of innovation to flourish.

With the European Union revising its pharmaceutical legislation, member states have a chance to leverage this initial work and harness their collective power to position the EU as hub of antimicrobial and policy innovation. This is a rare opportunity, and any pull incentive must be truly catalytic if it is to attract private investment to the region. This means a pull incentive should be sizable enough to convince investors and drugmakers that developing antimicrobials is worth the substantial risk associated with the products.

Lastly, if a pull incentive is going to elevate the regional biotech sector, policymakers must carefully consider what is feasible and achievable by drug developers when determining which antimicrobials will be eligible for contracts. Small- and mid-size biotechs are responsible for approximately 80 percent of antimicrobials in clinical development, according to the Biotechnology Innovation Organization[6]. Drug development is complex and takes time, and many of these companies have limited resources. Their ambition to develop lifesaving antimicrobials and replenish the pipeline should not be diminished by unrealistic expectations of innovation.

The advent of antibiotics was one of the fundamental drivers of the shift in health care that has dramatically increased life expectancy and improved quality of life. But microbes will always evolve, and so must our policies if we are to stay ahead of the threat they pose.

[1] https://www.g7germany.de/resource/blob/974430/2042058/5651daa321517b089cdccfaffd1e37a1/2022-05-20-g7-health-ministers-communique-data.pdf?download=1

[2] https://www.g7germany.de/resource/blob/974430/2042058/5651daa321517b089cdccfaffd1e37a1/2022-05-20-g7-health-ministers-communique-data.pdf?download=1

[3] https://www.bio.org/press-release/new-bio-report-examines-state-antibacterial-innovation

[4] https://www.bio.org/press-release/new-bio-report-examines-state-antibacterial-innovation

[5] https://www.bio.org/press-release/new-bio-report-examines-state-antibacterial-innovation

[6] https://www.bio.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/BIO-Antibacterial-Report-2022.pdf